I spent Feb. 23 to March 6 in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, an island nation halfway between Hawaii and Australia. It was weirdly easy to get there: A nonstop United flight from Dulles to Honolulu, then a five-hour flight from Honolulu farther into the Pacific to Majuro, the capital of the RMI. With an unavoidable overnight layover and the time warp of the International Dateline, it took 48 hours to get there from the East Coast. It is certainly the most isolated place I've ever been. The islands are actually thin ribbons of low-lying atolls — coral foundations that have grown upward from the rims of ancient sunken volcanos. Landing on one in a commercial jet felt like driving a car onto a tightrope. All blue emptiness on either side, then narrow solid ground at the last second. Don't take my word for it. Take Google Earth's:

The RMI flew onto my radar last year when it filed a lawsuit against the United States. The charge was violating the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, a nearly 50-year-old agreement between nuclear-armed states and most of the rest of the world. The United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, China and France pledged to negotiate the elimination of their nuclear weapons if other signatories refrained from developing their own. Fast forward to 2015 and there are now nine nuclear-armed nations with a total of 14,000+ nuclear weapons among them (though the U.S. and Russia possess 93 percent of the total). The number of weapons is much less than the Cold-War peak, but the armed nations are modernizing and reinvesting in their existing stockpiles. This doesn't sit well with the Marshall Islands, which was the U.S. test site for 67 nuclear detonations from 1946 to 1958. The combined power of these tests, if parceled evenly over those 12 years, equals 1.6 Hiroshima-caliber explosions per day. One and a half Hiroshimas. Every day. For 12 years! The largest test was this one:

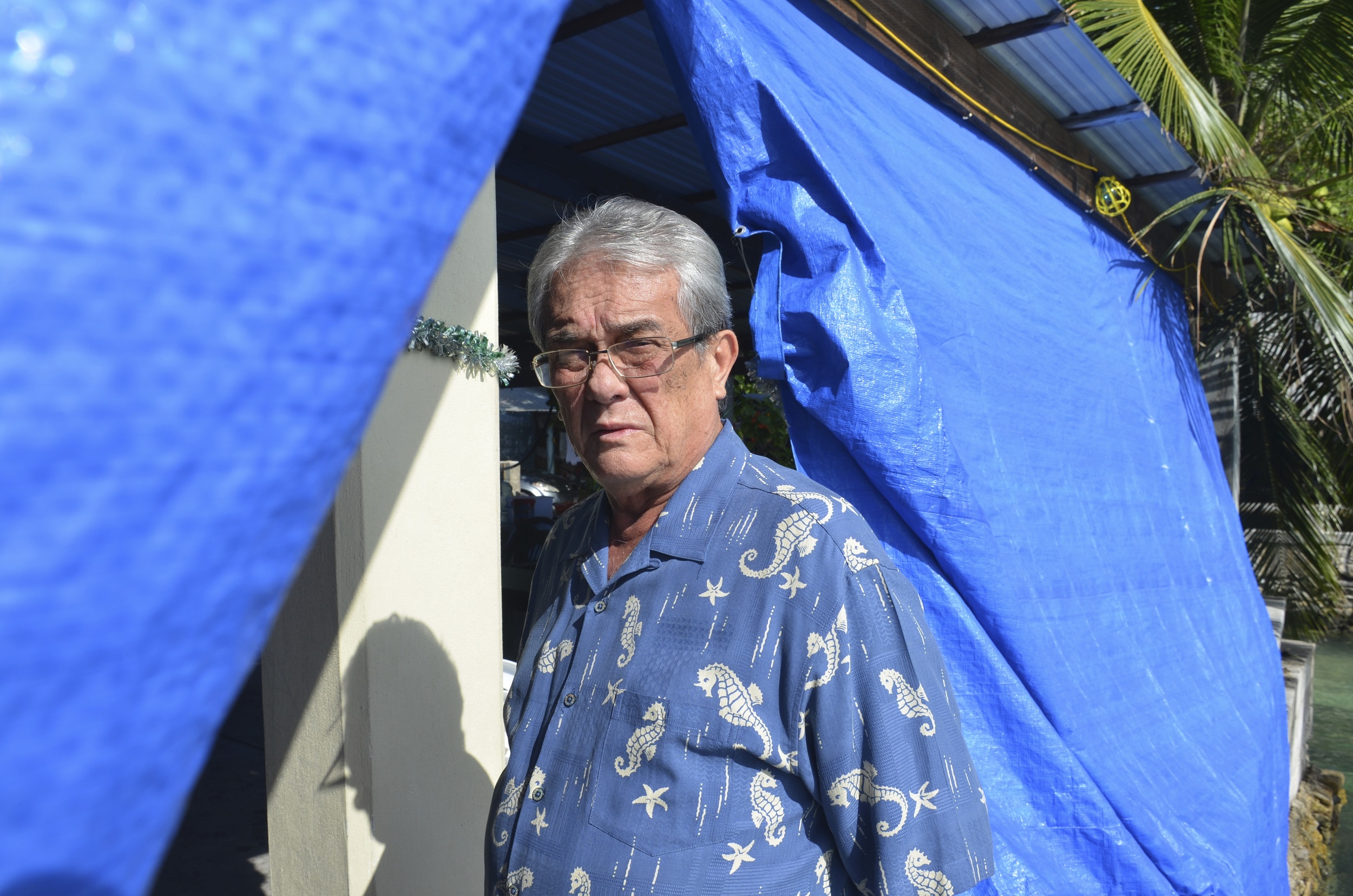

That's a four-mile-wide fireball. The light from the blast was seen from Okinawa, 2,600 miles away. The radioactive fallout was later detected in cattle in Tennessee. The detonations were somewhat inconceivable, particularly because there wasn't concrete destruction in the form of wasted cities. The damage was more insidious and longer-lasting. The U.S. shuffled the Marshallese around to make way for the tests, though not far enough away to spare them from fallout. We took a mini civilization and upset their harmonic relationship with nature, made them dependent on both money and medical treatment, and created a culture of victimhood and dependency. I don't mean to ignore the beauty and pride of the Marshallese people and customs. They endure. But the United States has had a profound effect on these wisps of land in the Pacific, and I wanted to visit and write about their tortured relationship with Washington and their unique confrontation of the planet's only two existential crises: nuclear warfare and climate change, which is causing sea-level rise. The RMI is really the only nation on Earth to have experienced both acutely, though testing affected everyone in the United States to a degree: A 2002 study submitted to Congress reported that "Any person living in the contiguous United States since 1951 has been exposed to radioactive fallout, and all organs and tissues of the body have received some radiation exposure." This animated graphic plots the 2,054 nuclear tests conducted around the world since 1945.

Here's the annual king tide last year in Majuro (a tide, not a tsunami):

What was most head-spinning, for me, was the fact that the United States still uses the RMI for military testing. Obviously we're not detonating nuclear weapons there, but we do use Kwajalein Atoll for nuclear target practice. Here's video of an intercontinental ballistic missile (unarmed, of course) being launched from California toward Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands in May of this year:

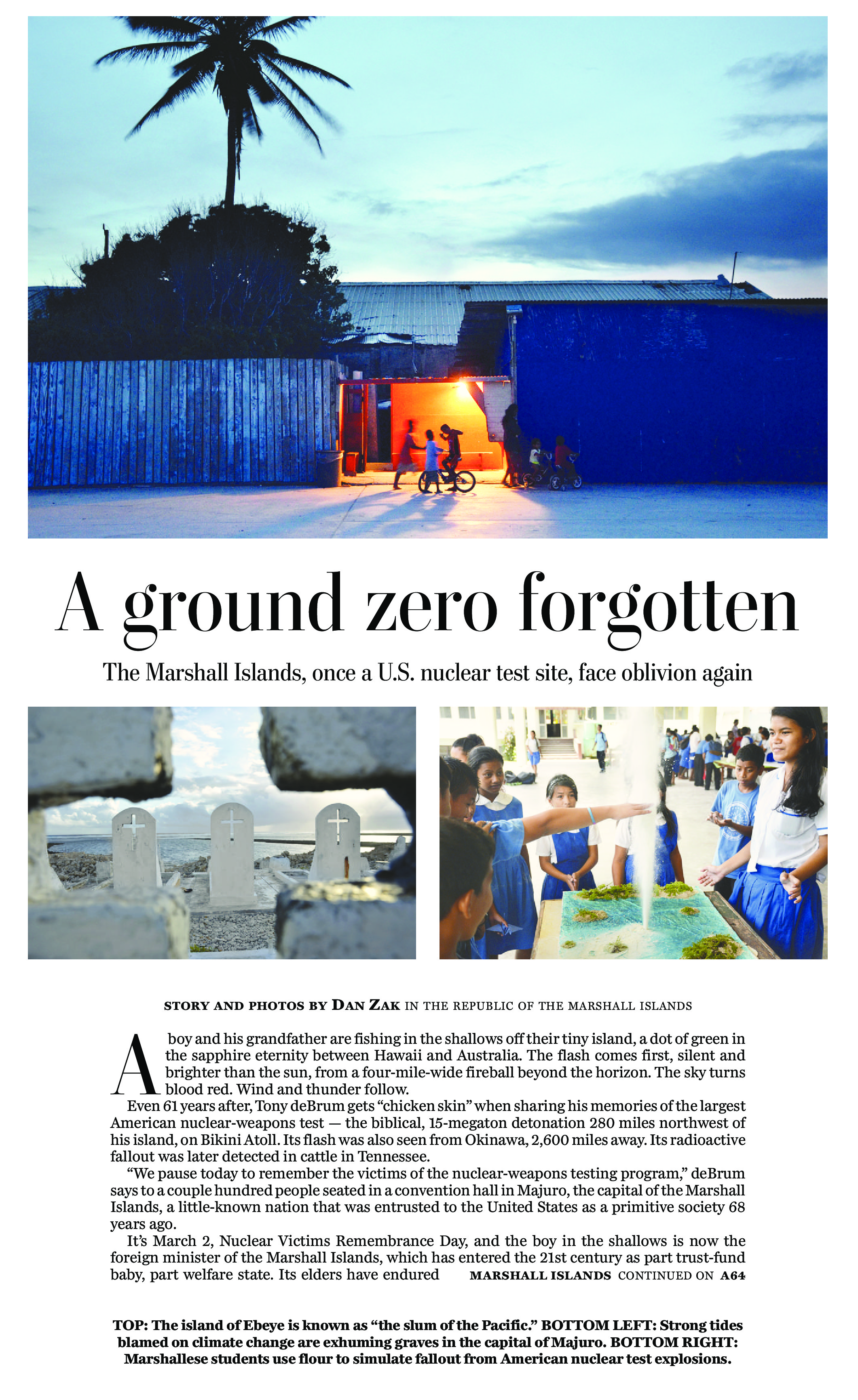

Anyway, I was only in the RMI for a week and a half, but this story and these photos are the result. Needless to say, a newspaper article only scratches the surface of a staggeringly complicated situation and a generous and resilient people. It all deserves its own book. Thanks to the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting for funding the trip. Here's a selection of my photos:

And here is how it was initially designed for the front page by the Post's Robert Davis: