I finished George Packer's "The Unwinding" about the same time he won the National Book Award for non-fiction last week -- a fitting distinction because this is truly a national book. It attempts to diagnose what ails We the People through a series of case studies: 10 celebrities, nine years (plotted between 1978 and 2012), three locations (Tampa, Silicon Valley and Wall Street) and three ordinary citizens (a female African-American factory worker in Ohio, a rural entrepreneur in North Carolina and a campaign staffer turned lobbyist associated with Joe Biden). Packer apportions these citizens' life stories over several chapters throughout the book but only devotes a single chapter to each famous person. His casting of the bold-faced names is both obvious and curious, and he uses each mini-profile to say something about the erosion of the country.

Newt Gingrich, "a man whose America stood forever at a historic crossroads, its civilization in perpetual peril."

Oprah Winfrey "exalted openness and authenticity, but she could afford them on her own terms."

"By paying attention to the lives of marginal, lost people, people who scarcely figured and were rarely taken seriously in contemporary American fiction," Raymond Carver "had his fingers on the pulse of a deeper loneliness."

"The small towns where [Sam Walton] had seen his opportunity were getting poorer, which meant that consumers there depended more and more on everyday low prices, and made every last purchase at Wal-Mart, and maybe had to work there too."

Colin Powell "was trying to function inside institutional failure" where "statesmen and generals had become consultants and pundits."

When Alice Waters "heard the criticisms, she turned away, to the radishes and the flowers. Anyone who was passionate enough about organic strawberries, she believed, could afford to buy them."

The period when Robert Rubin "stood at the top of Wall Street and Washington was the age of inequality -- hereditary inequality beyond anything the country had seen since the 19th century."

Jay-Z "had to keep winning. Success wasn't about anything except itself."

For Andrew Breitbart, "Old Media's rules about truth and objectivity were dead. What mattered was getting maximum bang from a story, changing the narrative."

Elizabeth Warren's "very presence made insiders uneasy because it reminded them of the cozy corruption that had become the normal way of doing business around Capitol Hill. And that was unforgivable."

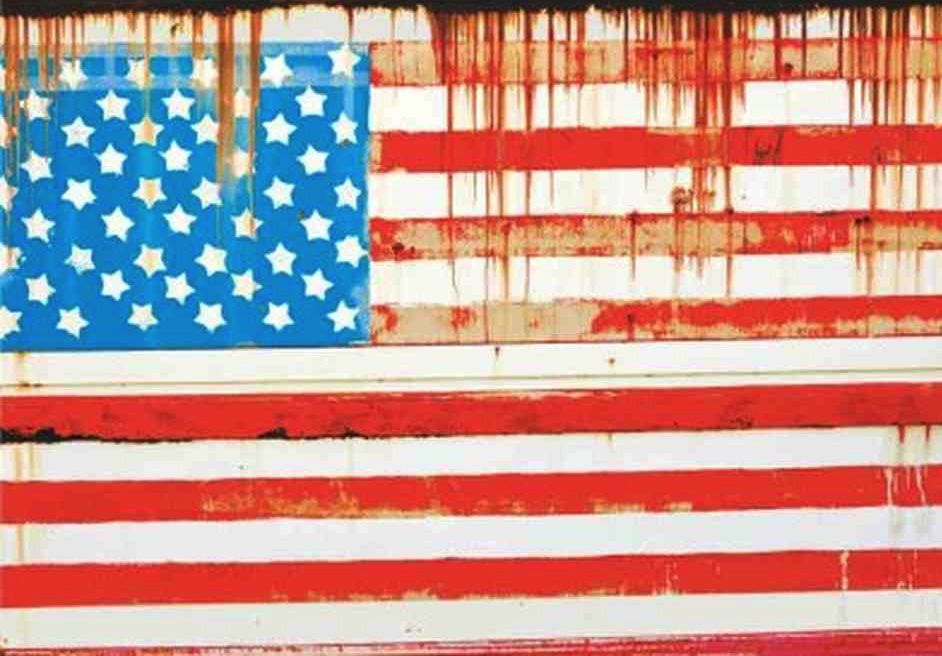

The thread here is corruption: of politics, of economics, of media. Corruption, Packer illustrates, is corrosion, and the first people to wash away are people like his citizen characters: Dean Price, Jeff Connaughton and Tammy Thomas. Sometimes one person's pursuit of happiness, Packer implies, derails another's -- at least in the America of the past 35 years, where winning means winning big and losing means losing everything. "This much freedom," he writers in his very brief introduction, "leaves you on your own."

Too much freedom? Treason! And yet truth. Americans are possessive of the idea and the memory of their country, even if the idea is imperfect and the memory is inaccurate; how many times has someone been quoted -- especially in the last five years -- as believing that they've lost their country, or that they want their country back, or that the government is coming for them in some way? Most times, I think, this sense of loss is wired too closely to nostalgia, and paranoia results. Packer acknowledges this and moves it aside, aiming for a notion more universal than one person or demographic's varnished perspective. What exactly is unwinding? The middle class, you might say, but Packer suggests broader stakes. The social contract and the golden rule are unwinding.

The book's subtitle is key: "An Inner History of the New America." Packer burrows into the brains and hearts of his subjects, even when his only access to them is roundabout. "The biographical sketches of famous people are drawn entirely from secondary sources," he writes in the afterward, where he also cites as literary inspiration John Dos Passos' "U.S.A." trilogy, heretofore unknown to me. Packer shares with Dos Passos a bifocal view of the country. The foreground is an impoverished mess and the horizon is a shining city. "The Unwinding" is written on the glassy seam between two lenses, and the overall effect is both clarifying and dizzying. Packer's last chapter is centered on Dean Price, that rural entrepreneur in North Carolina who wants so badly to make a green economy work for his state but is repeatedly stymied by monied interests and an underemployed public trained to be suspicious of change. I can't decide if the final page -- in which Price dreams of making a fortune by selling cooking waste to biodiesel companies -- is hopeful or rueful about the New America. This, maybe, is Packer's genius. After all, the American dream, in its current state as illustrated by Packer, has become contingent on both American corruption and American idealism.

Lastly, because it shows Packer's muscular command of the inner and the outer and because the first sentence aptly describes his own reporting and writing, I'll excerpt this paragraph from p. 176:

[Dean Price] was seeing beyond the surfaces of the land to its hidden truths. Some nights he sat up late on his front porch with a glass of Jack and listened to the trucks heading south on 220, carrying crates of live chickens to the slaughterhouses -- always under cover of darkness, like a vast and shameful trafficking -- chickens pumped full of hormones that left them too big to walk -- and he thought how these same chickens might return from their destination as pieces of meat to the floodlit Bojangles' up the hill from his house, and that meat would be drowned in the bubbling fryers by employees whose hatred of the job would leak into the cooked food, and that food would be served up and eaten by customers who would grow obese and end up in the hospital in Greensboro with diabetes or heart failure, a burden to the public, and later Dean would see them riding around the Mayodan Wal-Mart in electric carts because they were too heavy to walk the aisles of a Supercenter, just like hormone-fed chickens.